Will the river remember

the land we lost?

2020

A fragment of research prepared for Before I Knew You for Haus der Kulturen der Welt's Mississippi: An Anthropocene River.

I do not know much about gods; but I think that the river

Is a strong brown god - sullen, untamed and intractable,

Patient to some degree, at first recognized as a frontier,

Useful, untrustworthy, as a conveyor of commerce,

Then only a problem confronting the builder of bridges.

The problem once solved, the brown god is almost forgotten

By the dwellers of cities - ever, however, implacable,

Keeping his seasons and rages, destroyer, reminder

Of what men choose to forget.

– T.S. Eliot, “Dry Salvages,” Four Quartets, 1941.

Before I knew her,

the Mississippi River was a magnificent existent—“a strong brown god.” As she saunters from her headwaters in the body of land we call Minnesota to her mouth in the body of water we call the Gulf of Mexico, she gathers strength, growing in magnitude, swelling with the sedimented pride of her progeny: place. Yet along her journey, she is straightened and shackled, as the Army Corps of Engineers once boasted, by a system of levees, locks and dams. The longer she travels, her waters are aged, burdened, depleted by an onslaught of fertilizer runoff, plastic nurdles, petrochemical waste—the byproducts of the fossil fuel economy. Prevented from feeding fresh sediment to nurture her wetlands, her mouth instead spews forth a 7,000 square-mile hypoxic Dead Zone into the Gulf.

In September 2019, I traveled along the River’s headwaters in Minnesota—the only portion of her length that is protected as a national park—via a 24-foot voyager canoe. This part of the River’s body exists prior to the Petrochemical Corridor, which stretches through Louisiana, my homeland. In Minnesota, the Ojibwe, Ho-Chunk, and Dakota nations have pressed the State government to begin the process of dismantling her restraints. The Mississippi’s headwaters carry visions of her temporal origins, which wink into potential futures as US society reckons with the violence of its existence. Riding these young waters felt like greeting a River I’d never had the honor to meet, even though she was the same River I’d always known, the same River that gave birth to my people and my place. The one and only strong brown god that can rebuild our future.

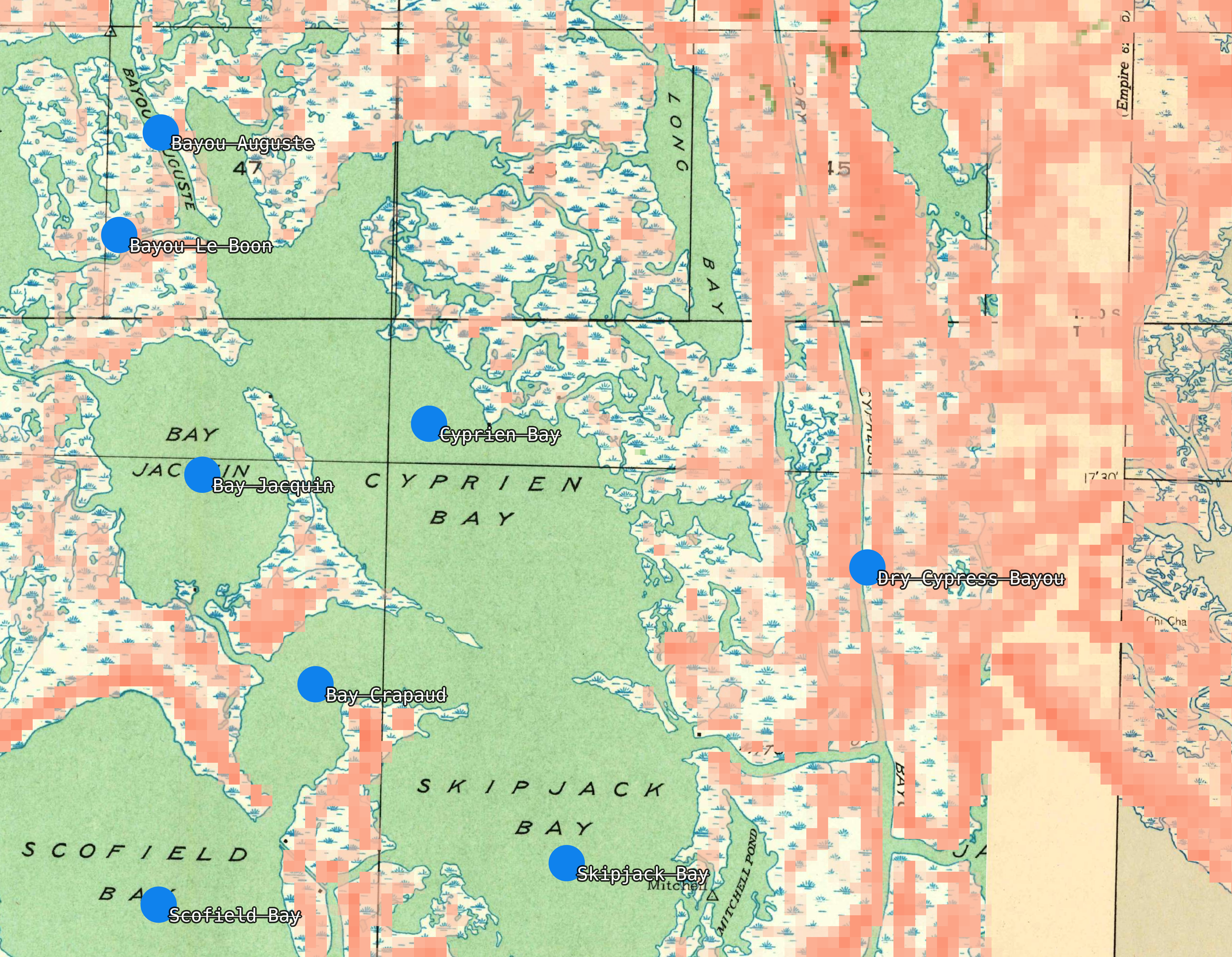

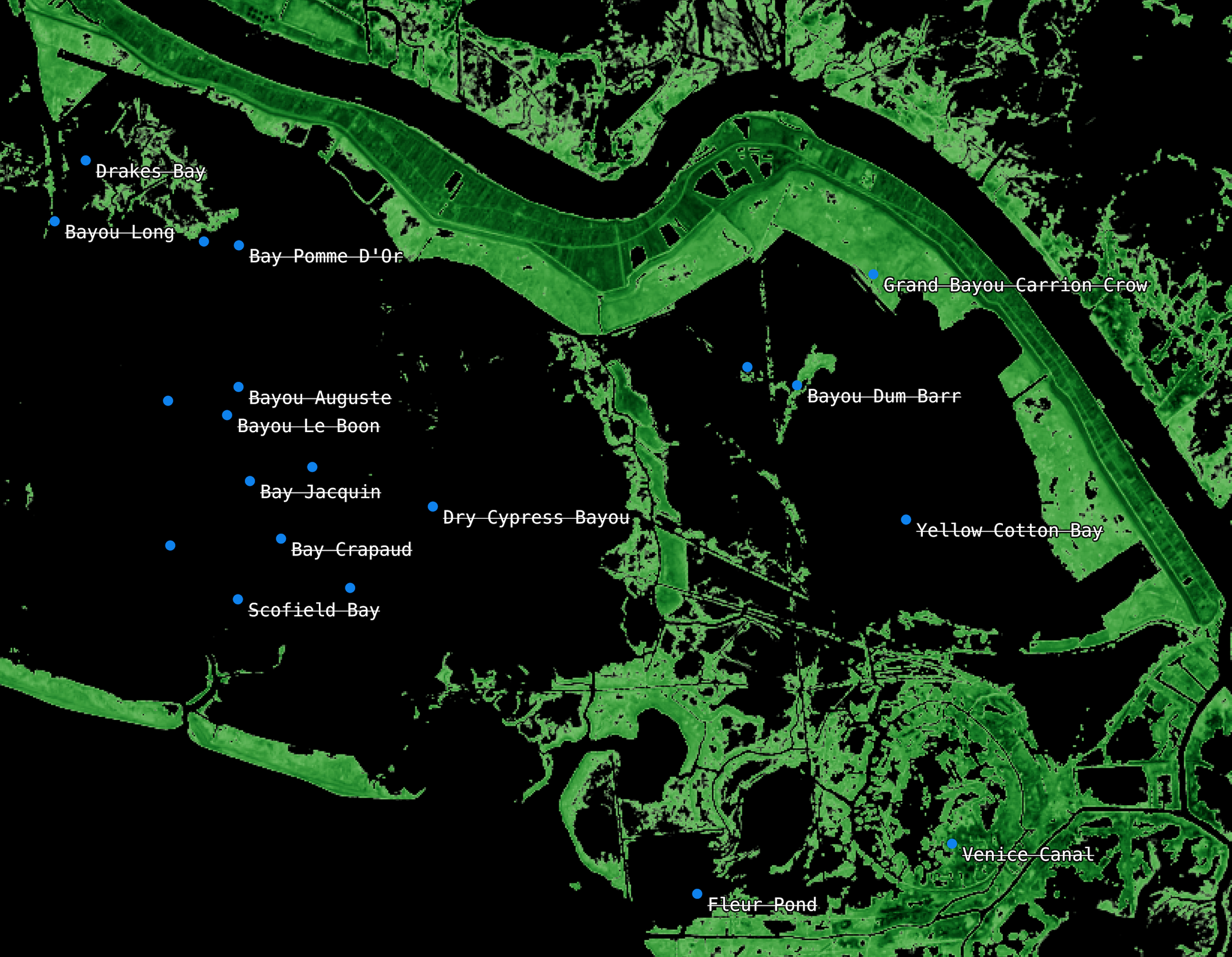

In January 2020, I traveled above the River’s mouth in Louisiana via a three-passenger plane to survey the violence wrought against her Delta by the fossil fuel industry’s greed. For 7,000 years, the River carried alluvial sediment, slowly building our Delta. Beginning in the 18th century, enslaved Africans dispossessed of their homelands were forced to displace land to carve a corset of riverside plantations. Over the past 100 years, a network of 10,000 miles of oil and gas access canals have caused this land, along with its settler-colonial names, to disintegrate into the sea. The Mississippi’s Birdsfoot Delta stretches into the Gulf like the wasted talons of a bird of prey in search of fish that have long since died off.

Displacement of people prefigures the displacement of sediment prefigures the displacement of people...

Will the River remember the land that we lost?